Blitzkrieg Bop: 1976 and the Birth of Punk

Click below on the streaming service of your choice to listen to the playlist as your read along.

Punk music is one of the most interesting topics of rock music to explore. Its arrival was one of the most sudden, disruptive, and course-altering forms of rock music ever and swept in the era of modern music as explored in 1977: The Birth of Modern Rock. Of course, no new music style ever arrives fully formed and completely divorced from the past, and the various evolutions and contributions to punk’s arrival were covered in the profiles on the Builders of Modern Rock and the two-part profile on glam rock. To follow the journey from rock ‘n’ roll’s formation to the arrival of modern rock, you’re encouraged to read these profiles.

The Playlist - artist \ song (month of release)

The Ramones \ Blitzkrieg Bop (Feb)

Blondie \ X Offender (Jun)

The Saints \ (I’m) Stranded (Sep)

Patti Smith \ Ask the Angels (Oct)

The Damned \ New Rose (Oct)

The Vibrators \ Whips and Furs (Nov)

Richard Hell & The Voidoids \ Blank Generation (Nov)

Sex Pistols \ Anarchy in the UK (Nov)

Pere Ubu \ Final Solution

Crime \ Hot Wire My Heart

Punk rock was both a tribute to and a rejection of the various forms of rock that came before, in some cases as a contradictory mix of the same music, such as glam. Such feelings also existed when it came to music, as popular and evolving strains of rock music were getting more sophisticated, expansive in sound and composition, and requiring greater numbers of musicians and studio resources to produce. There had always been a manufactured segment of the music industry filled with artists tightly managed, produced, and promoted for maximum exposure and sales. By the mid-1970s rock had been taken over by the major labels looking to cash in on its rise in prominence since the ‘60s. This form of ‘corporate rock’ had, not surprisingly, been migrating the rock sound into more palatable, less confronting, smoother compositions and moods, filled with sweetness and light built on strings and sweetly sung voices and harmonies. Aspiring musicians with little money or access to instruments and lessons, venues, studios and producers, or ways to express their daily frustration, took what they could and began playing a stripped down, aggressive, direct form of rock. Out of this developed the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, in which permission was no longer sought from the traditional gatekeepers for music distribution or the tastemakers of popular culture. Punks got their music out whether it was well played or not, recorded well or not, or anointed by a major label or the music media or not. They forged ahead directly to the public with their own clubs, labels, and fanzines in order to create a whole new culture in which the music industry and broader culture had to reckon with, whether they wanted to or not.

Punk’s musical tributes were to the original rock ‘n’ rollers of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, the garage rock and mod acts of the mid-60s, and the proto-punk , pub rock, and power pop artists of the early ‘70s. The early punk bands, before they wrote their own songs, all played the songs of the ‘50s and ‘60s that were featured in the Builders profile, and very often covered them in their shows and on their albums, in the same way the early ‘60s British Invasion bands had done upon their arrival. Punk’s rejection was of the saccharine corporate rock, the showiness of glam, and the pomposity of prog rock. It was a return to the simpler, more accessible form of rock n’ roll, only cranked up to a new fever pitch.

Punk was also sociological and political, also rejecting the societal forces and government policies that had rendered large segments of the working class and poor as disadvantaged, disenfranchised, and with diminished prospects for success. The music was angry and aggressive because its players were angry and wanted people to know it. Punk was a clarion call for change not just in music but in how society was structured.

There was also fashion, even if it too was based on rejection more than promotion. There would be no smartly dressed bands, suits or dresses, nor blow-dried and perfectly coiffed hairdos. Punks revelled as much in using clothing and style to shock and confront as glam had, or even as the late ‘60s psychedelic and hard rock acts had done, but did it by adopting an aesthetic that was as anti-conformity as possible, whether it was ripped clothing, incendiary symbolism, messy or bizarrely styled hair and colours, and jewellery and piercings that suggested a commitment to the fashion that transcended the temporal considerations of clothing or make-up. Punk didn’t just challenge with sound, it sought to shock and confront all the senses and make itself known by overturning everything people had been raised to believe as good and necessary to succeed in the world. It would look, sound, and behave dangerously, and in the same way glam had up-ended gender norms, would turn around the common expectations of music and talent, public behaviour, and who gets to have a say in how things should be.

Blitzkrieg Bop \ The Ramones (February)

As the first to definitively exhibit what would become known as punk culture, The Ramones would start things simply. The band was formed in the New York borough of Queens among four men who knew each other from high school and through bands they’d played in together. John Cummings and Thomas Erdelyi had been in a garage band together in the ‘60s while in high school and they knew Doug Colvin and Jeff Hyman from the neighbourhood. Hyman was the singer in a glam band called Sniper. Cummings and Colvin joined with Hyman to form a band in 1974, with Cummings on bass, Colvin on guitar and vocals and Hyman on drums. Soon after Colvin realized he couldn’t sing and play guitar, so Hyman took on the vocals, also soon realizing that drumming and singing were a tough prospect together, so he stepped out from behind the kit to take on the vocals exclusively. Left without a drummer, Erdelyi, who had been acting as the band’s manager, would step in during rehearsals until it was decided to make him the full-time drummer.

Colvin suggested the band adopt stage names, with his preferred name being Dee Dee Ramone, taken from an alias Paul McCartney had used (Paul Ramon) in his pre-Beatles career. Colvin further suggested they all adopt the Ramone name and thus the band would be: The Ramones. Thus, Hyman became Joey Ramone, Cummings was Johnny Ramone, and Erdelyi adopted Tommy Ramone when he joined the band.

Johnny, Tommy, Joey, and Dee Dee

The four Ramones, at the time the band was started, were between the ages of 23 and 26, and their musical inspirations reached a little further back to the rock and pop music of the ‘50s and ‘60s – Joey in particular loved the Phil Spector wall of sound and the girl groups he produced, such as The Shangri-Las and The Ronettes. The band naturally adopted a pop style with short, catchy songs similar to the music of that era. However, having been more recently influenced by the heavier and raw sounds of The Stooges, MC5, and New York Dolls, the songs were played with a heavy sound. The band liked this approach since it was the opposite of the prevailing forms of rock in 1974-75, which they all disliked. Since they were all from the affluent area of Forest Hills in Queens, their rebellious approach was strictly musical. Dee Dee, though now on bass, continued his original habit from when on vocals of counting in the songs in with a quick 1-2-3-4 before the band would rip through the songs in about two minutes or less at a fast and driving pace. It was direct, catchy, without nuance, and without any embellishment.

The minimalism of their music extended to their fashion as the band adopted a uniform look in the spirit of their ‘Ramone family’ dynamic. They took on the look of their early ‘60s musical influences by all wearing jeans, t-shirts, running shoes, and leather jackets. The only deviation was the long hair of the later ‘60s and early ‘70s.

The Ramones joined with a growing contingent of avant garde and non-conforming musical acts that were coalescing around the venues CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City, as discussed in the Builders playlist. There wasn’t a prevailing look or sound across these acts, though several were adopting the rougher sounds and look that separated them from the current mainstream music. The Ramones stood out due to their unrivalled energy, pacing, and stripped down style. Joey in particular, with his long hair and long, lean, 6’ 6” frame made for a striking presence in the small clubs. There simply wasn’t any rock band around – then or before – that played with their speed and ferocity; and the songs started at that pace and ran straight through, ending as abruptly as they started. On their first album, there wasn’t a single slow song. From today’s perspective their music doesn’t seem that fast or hard, but it was miles different than what was common at the time.

Seymour Stein signed the band to his label, Sire Records, in late 1975 recognizing that of this burgeoning New York scene, The Ramones were an exciting and unique act. Their first single was the now iconic, “Blitzkrieg Bop,” recorded in January of 1976 and released the next month. The self-titled album followed in April, and while the local New York scene loved them, they were just too different and too aggressive to catch on. The album, now recognized as one of the most influential and ground breaking LPs in music history, didn’t crack the top 100 in the US charts. Likewise, “Blitzkrieg Bop” and its follow-up, “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend,” didn’t chart.

Punk was an evolving term and concept, and in the early days it was used more loosely to collect together the various sounds and artists of the New York underground scene. The term had made appearances in English for a few centuries, usually as a derogatory or slang term for prostitutes or young ruffians. By the early ‘70s it was not uncommon for adults to refer to troublesome young people, criminals, or other miscreants as a ‘punk’ or ‘young punk.’ Artists in the rough edges of the music scene and those writing about it started referring to the musicians, music, and shows through punk references. After Lenny Kaye referred to the garage bands of the ‘60s as punks in his seminal 1972 compilation album, Nuggets, various bands started to be described as punk rock and a magazine devoted to that era was began in 1973, called Punk Magazine. It didn’t last long but a fanzine of the same name began in December 1975, this time focused on the current, local New York music scene and the name started to be adopted as a colloquial moniker. However, whether it was the New York Dolls or many other, different rock acts of the time, the term was more of a descriptor and didn’t embody a defined musical concept. The Dolls were as often seen as glam, or even glam-punk, which was the established genre in the UK by then though still more of a fringe thing in the US.

Upon The Ramones debut in February 1976, lets take a look at what was topping the charts in the US at the time. This was the top ten for the week of February 28, 1976.

Theme from S.W.A.T. \ Rhythm Heritage

50 Ways to Leave Your Lover \ Paul Simon – had just dropped out of #1 after 3 weeks

Love Machine (Part 1) \ The Miracles

All by Myself \ Eric Carmen

December 1963 (Oh, What A Night) \ The 4 Seasons

You Sexy Thing \ Hot Chocolate

Take It to the Limit \ The Eagles

Dream Weaver \ Gary Wright

Lonely Night (Angel Face) \ Captain & Tenille

Love Hurts \ Nazareth

Also in the top ten that month,

Love to Love You Baby \Donna Summer

Sing A Song \ Earth, Wind and Fire

I Write the Songs \ Barry Manilow

Love Rollercoaster \ Ohio Players

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do \ Neil Sedaka

Evil Woman \ Electric Light Orchestra

After Patti Smith and Television, The Ramones were the next act of the New York and CBGBs scene to be signed and to release music. Their sound was so different from everything else that was around it demanded a new definition. Of course, it would take a while for the genre to mold into something cohesive and it helped that so many bands quickly followed in The Ramones footsteps, especially in the UK, such that a year or two later, in hindsight, it was clear that what became definitively known as punk started with the arrival of The Ramones.

X Offender \ Blondie (June)

Joey Ramone & Debbie Harry at CBGBs

Blondie was another band that came together from various musicians that had been playing in the New York scene for a while, and therefore like The Ramones were a bit older and drew further back for their influences. They were started by the couple of Chris Stein and Deborah Harry, who came out of the band, The Stilettoes, and called their new act Blondie after the catcalls Debbie would receive on the streets of New York. They also played at CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City and their sound married the artsy and aggressive New York vibes with a retro ‘60s sound. They had a more refined pop sensibility, softened by the use of keyboards and Harry’s voice, as well as her undeniable charisma and appeal. As the sense developed of what was punk or not, Blondie would not easily fit within its musical boundaries but their look, attitude, and energy fit more with punk than anything else.

They signed with a small indie label, Private Stock Records, and released their first single in June 1976, “X Offender,” followed by “In the Flesh” in October and then their self-titled album in December. “X Offender” was the best example of their punk energy merged with the ‘60s pop sound. “In the Flesh” was an unabashed retro-pop slow song, smoothing over any punk overtones, and brought them a #2 chart placing in Australia and eventually a #14 spot for the album. The LP was very good but not a future classic as the band was still forming their sound and figuring out their identity. In the US, UK, and other countries it would take a couple more albums to warm up to them as Blondie made their way to huge career success, by far the biggest of any of the New York punk bands. For a more extensive history of Blondie, check out their Ceremony profile.

(I’m) Stranded \ The Saints (September)

Speaking of Australia, it was developing its own underground scene of aggressive rock bands, most notably out of Brisbane with The Saints. They were formed in 1974 by teenagers Chris Bailey, Ed Kuepper, and Ivor Hay. The parallels to The Ramones were not surprising. They were raised on the garage rock and pop of the ‘50s and ‘60s and then influenced by more recent acts like The Stooges and MC5. They liked to play shorter, fast, pop-styled songs. Their songs weren’t as short as The Ramones and they mixed in some slow and mid-tempo songs, but when they cranked it up they played just as fast as the New Yorkers.

The Saints

The Saints are particularly important because they embodied an element of punk that became a defining characteristic. As I noted in the introduction, punk artists were often disenfranchised and on the outside of the scenes from which bands were getting label interest, not the least of which because their sound was so far from what was popular. At least in their case, The Saints weren’t as different looking as other standard issue rock bands. Not getting any interest in their sound, the band formed their own label, Fatal Records, and got the money together to record two songs, “(I’m) Stranded” and “No Time.” This do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos became an integral part of punk culture and fit with the independent, non-conforming spirit of the music and fashion.

“(I’m) Stranded” was released in September and was the first punk song to be released outside the US. It was simply an incredible tune with an impeccable melody, ferocious, kinetic pace, and Bailey’s snarling, flat-toned vocal. While Australian audiences were indifferent, legendary British DJ John Peel played them on his show, which led to a following in the UK and major label EMI to instruct its Australian subsidiary to sign them up. They released their first album, (I’m) Stranded, in February 1977. Like other early punk acts, the song and album didn’t make a ripple in the charts, north or south of the equator, which was a shame because it’s another classic album that influenced a generation of bands that followed and helped to build on The Ramones release in galvanizing this new sound. I’m especially taken with the down tempo song, “Messin’ with the Kid,” that blended a classic rock feel and Dylanesque phrasing with the indifferent vocal tone, looseness, and raw guitars of the punk sound. The Saints, with this album, established themselves as one of the earliest and more influential acts of the punk era, all the way from the southern hemisphere.

Ask the Angels \ Patti Smith (October)

As you can see, despite 1976 being ground zero for the arrival of punk, by the last quarter of the year there had really only been two punk songs issued, both of which had been roundly ignored, and Blondie’s punkish take on the retro-pop sound. So, lest there be any impressions that punk arrived in a fury and set the world on fire, that was not the case. However, it was building a respectful coterie of critics and fans that, along with other emerging sounds as documented in the last parts of the Builders of Modern Rock playlist, were turning away from the mainstream options and its hangers-on and embracing this exciting new sound. One of those gaining a following and blazing a trail, and just the second woman on our list (read more about women’s contributions to modern rock’s early days in this profile on women in modern rock), was Patti Smith. You can also read a more extensive profile on Patti here.

Smith’s debut album, 1975’s Horses, was also discussed in the Builders profile, and with it she’d gained attention as an interesting and talented artist, blending her street poetry with rock licks and flavoured with her amazing vocals. The album cracked the top 50 in the US charts, making her one of the first and a rare artist of the New York scene to achieve broader popularity. Perhaps that was because the album, musically, had more of a traditional rock foundation, and the punk vibe was only ventured towards on a few tracks.

Patti was also from the CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City scene, partnering with her guitarist, Lenny Kaye. The first unabashed punk song she released was in March 1976 and it was her live cover of The Who’s “My Generation.” It was the B-side to the single, “Gloria,” which had been the lead track on her debut album. Over the course of 1976 she would release two singles, “Pissing in A River” and “Pumping (My Heart),” both from her second album, Radio Ethopia, released in October. The first was a rock ballad while the second was an energetic rock song, but while everything Patti sang sounded cool, neither displayed the characteristic punk edge. It was the album’s lead track and third single (not released until early ’77), “Ask the Angels,” in which Patti reminded listeners of her punk credentials and added to the nascent punk canon. It was a powerhouse of a song, vast sounding, edgy, and as always driven by Smith’s remarkable performance.

New Rose \ The Damned (October)

Although punk started in America, the stereotype of the punk sound, look, and attitude came mostly from the British punk scene. Like the trends in the US, many British youth were gravitating to harder and edgier music and had long embraced harder rock sounds compared to American audiences. The economic conditions in Britain in 1975 and 1976 were bleak, and the counterculture in London, like New York, was coalescing around a few clothing shops and live music clubs, especially the 100 Club. When The Ramones toured the UK in the summer of 1976, most notably with a show at The Roundhouse on July 4 opening for The Flamin’ Groovies, the punk scene in London really started to take hold. Not only did it launch many bands in England, it raised the prominence of The Ramones and boosted their career also. Like garage rock and glam, this alternative music found a more ready fan base in the UK than in the US.

Central to the formation and promotion of the London punk scene was Malcolm McLaren, who was like a maestro in tapping into the shifting underground trends of England. Along with his girlfriend, clothing designer Vivienne Westwood, they ran a shop on the King’s Road in Chelsea, London. It started in 1971 as ‘Let It Rock’ and focused on retro ‘50s and ‘60s Teddy Boy themes, then shifted in 1972 to ‘60s rocker-inspired clothing under the name, ‘Too Fast to Live, Too Fast to Die’, before renaming and shifting again in 1974 into ‘SEX,’ which included bondage and fetish inspired clothing. McLaren also had an interest in the music scene and started managing bands mostly made up of the young men and women that were hanging around both his shop and John Krivine and Steph Raynor’s ‘Acme Attractions’ just down the King’s Road.

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood

Their clothing shop on the King’s Road, SEX, with employee and punk fashion plate, Jordan, mystifying the locals

McLaren spent time in New York through late ’74 and early ‘75, during which time he informally managed the New York Dolls, who by that point were on their way towards disbanding. His brief management and promotion of their career didn’t save the band from their fate but did allow him to immerse himself in the New York underground scene of CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City. Exposed to the likes of The Ramones and Richard Hell, he returned to London in May of ’75 keen to bring the look and sound of those acts to London.

One of the London bands McLaren managed was Masters of the Backside, who never got beyond rehearsals but included American singer Chrissie Hynde as well as David Lett, Raymond Burns, and Chris Millar. Brian James, who was in a band called London SS along with Mick Jones (later of The Clash) and Tony James (later of Generation X), also never got beyond rehearsals but did record at least one demo, and are best known historically as having auditioned and passed over a who’s who of the later punk scene, such as The Clash’s Paul Simonen, Terry Chimes, and Topper Headon, and the above noted Chris Millar. Brian James and Chris Millar decided to start their own band and soon added Dave Vanian (who got the gig when Sid Vicious failed to show for the audition) and Raymond Burns to the line-up. While Vanian and James stuck with their names, Millar and Burns went by the stage names Rat Scabies and Captain Sensible respectively. The new band was formed in early 1976 and was called The Damned.

The Damned in 1976: Dave Vanian, Captain Sensible, Rat Scabies, and Brian James

Flyer for the Punk Special festival at the 100 Club

Central to the formation of the London punk scene was the 100 Club on Oxford St., which had been a live music venue since 1942 and featured swing and jazz. By the ‘70s it was hosting R&B acts and then rock acts, and by 1976 was embracing punk bands. The Damned’s first show was there on July 6, just two days after The Ramones show, and included the Sex Pistols. In September, the 100 Club hosted the ‘100 Club Punk Special,’ a two day festival that showcased eight bands and served to definitively establish the punk genre and its name not just for London, but perhaps across the entire music world. The line-up was, on Monday the 20th: Subway Sect, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Clash, and the Sex Pistols. On Tuesday the 21st it was: Stinky Toys, Chris Spedding backed by The Vibrators, The Damned, and the Buzzcocks. Almost all of these bands were unsigned, only recently formed, and in some cases, still learning to play their instruments and songs. Regardless, the energy, look, and sound cemented the idea of a punk scene.

Modern rock is largely associated with indie music, being music released and promoted through smaller labels not associated with the major labels that have dominated the music industry. Originally the music industry was nothing but independent labels, but through consolidation and growth a few brands dominated the industry and become known as the majors. In 1976 the majors were Columbia-CBS, RCA, MCA, PolyGram, EMI (Electronic & Music Industries), and Warner Bros-WEA (Warner-Elektra-Atlantic).

Given their size and revenues it could be hoped a certain amount of risk could be tolerated by the majors, but with shareholders to keep happy, large payrolls including executive salaries and bonuses, and the need to fund extensive promotional campaigns for their artists, a risk averse culture was more the norm. Further, most musical acts failed, there is only so much room in people’s time and wallets to support music and only a few, relatively speaking, could get the larger amounts of attention and sales that filled the coffers of the major labels. Therefore, for every several failures that gave little to no return on the investment of recording and promoting them, there needed to be medium to large successes to recoup the losses. In terms of business strategy, it was eminently reasonable to focus on what would sell and bypass anything too risky that would almost certainly lead to losses. From a music and culture perspective it was short-sighted and left many talented acts in the shadows, narrowed the scope of music styles people were exposed to, and stifled innovation and the growth of new music.

Enter the indie labels, where in which the larger financial obligations of the majors were not a concern and were, as often as not, led by individuals and groups more focused on the music than the business which led to short lifespans and ignominious ends for more than a few, but along the way helped expose a lot of great and boundary expanding music. In 1976 Dave Robinson and Jake Riviera (Andrew Jakeman) were long-time artist managers, with Robinson having worked with Jimi Hendrix and Nick Lowe’s band, Brinsley Schwarz, while Riviera worked with Dr. Feelgood. Together they formed Stiff Records using a loan from Lee Brilleaux of Dr. Feelgood. As noted in the Builders profile, the label achieved early success with a single from Nick Lowe and then lesser return with a single by Pink Fairies. Drawing funds from their management business, they funded their third single, which was to be a momentous occasion for punk music and modern rock.

The single was The Damned’s “New Rose,” making it the first punk single to be released in the UK. Among the punk scene in which interest and momentum was growing and most of the attention was focused on the messy hijinks of the Sex Pistols, the release was a small coup for The Damned and Stiff. It helped that “New Rose” was a fantastic song. Like The Ramones, it was played at a furious pace, and while there was a solid melody, it was marked as much by a deeper, dangerous tone that thundered throughout and gave the song a wild, slightly unhinged quality, unlike the tight formations and pop influences of the first four songs on this playlist. The song captured the spirit in which London’s punk scene was becoming known, with its chaotic visuals, behaviour, and performances. “New Rose” announced an elevation of the punk genre to something beyond just faster rock ‘n’ roll, and by cracking the top 100 in the UK singles chart gave hope that the audience for this sound was more than just the Kings Road and Club 100 kids.

Whips and Furs \ The Vibrators (November)

The Vibrators were one of the many fledgling punk bands in London. They received a boost when Chris Spedding took them on briefly as his backing band. He was a journeyman guitarist that had played on numerous recordings for others, issued solo work, and worked with several bands since the late 1960s. He had a top ten hit in the UK with the rocker, “Motor Bikin’,” and over the course of 1976 played amongst the nascent punk scene in London, including the momentous 100 Club Punk Special with The Vibrators backing him. Together they would record a session for the John Peel show and back him on his single in November, “Pogo Dancing,” a reference to the punk dance style.

The Vibrators

It was on Spedding’s recommendation and their appearance at the 100 Club that Mickie Most signed The Vibrators to his indie label, RAK Records. Mickie Most is a name that appears often in the Ceremony glam playlists. The Vibrators issued their first single in the same month as their recordings with Spedding. The single was “We Vibrate,” a not very punky, bass-driven pop song but one that definitely had the swagger of punk. Its B-side was the wonderful “Whips and Furs,” a quick-paced pop-punk tune also carried along by a propulsive bassline.

The Vibrators’ singles, both their own and the one with Spedding, failed to chart. Yet punk was making headlines in the British media and was more notorious for its look and actions, but not yet its music.

Blank Generation \ Richard Hell & The Voidoids (November)

Back to New York, where as the year ended it remained a hotbed of musical innovation and a cultural explosion for 1970s America. One of the more enigmatic characters in that scene was Richard Meyers, better known as Richard Hell. His contributions had started in 1973 when he formed the band Television with Tom Verlaine (Tom Miller). He parted ways with the band in 1975 and then formed The Heartbreakers with Johnny Thunders of New York Dolls. That too didn’t last long, and Hell decided to form his own band with guitarists Robert Quine and Ivan Julian and drummer Marc Bell from Wayne County’s band, Backstreet Boys. Hell named the band The Voidoids after a novel he was writing.

Richard Hell & The Voidoids

Terry Ork was Television’s manager and also took on Richard Hell. He got his start in New York working on Andy Warhol’s movies in 1968. In 1975 he formed Ork Records, contributing to the independent, DIY punk spirit. The label released Television’s first single in 1975 as well as Hell’s first EP, which was the Another World 7” EP in November 1976. The A-side was the six-minute “(I Could Live with You) (In) Another World,” and on the B-side were two songs, “(I Belong to the) Blank Generation” and “You Gotta Lose.” Over time it would be “Blank Generation” that would become known as Hell’s signature song and one of the defining tracks of the era with its proclamation, “I belong to the blank generation / And I can take it or leave it each time.” It captured the indifferent and anarchic elements of the punk scene, dripping with its contempt and disgust for mainstream culture and society.

Hell was also a striking presence in the New York scene due to his appearance, which included spiked hair and ripped clothes held together with safety pins. It was this look that made an impact on Malcolm McLaren during his time in New York. He brought the minimalist, street style back to Vivienne Westwood and their shop, SEX, and it became a core part of their fashion.

Anarchy in the UK \ Sex Pistols

One of the earliest bands managed by Malcolm McLaren was the Strand, a pub rock band formed in 1973 that included Steve Jones on vocals, Paul Cook on drums, and Warwick ‘Wally’ Nightingale on guitar. They were progressing slowly as the young men learned to play their instruments, all of which were stolen from various other bands and played through microphones and a PA system nicked from David Bowie when he was playing the Hammersmith Odeon in July 1973. They hung out at the SEX clothing shop and in 1974 asked McLaren to manage them. One of the shop’s occasional (unpaid) employees, along with Nightingale, was Glen Matlock, who joined the band on bass. When McLaren headed off to New York he left Bernie Rhodes, who also worked at the store, to manage them and provide for their rehearsal space.

McLaren headed to New York in late ’74 in a state of despondency. The shop was struggling, his relationship with Westwood was in a rough patch, and London was getting him down. New York, which he’d visited for a short time recently, was an opportunity to see and hear new things and hopefully promote the clothing line. It seemed well ahead of London and shone like a beacon to his ambitious and mischievous self. This, with his extended stay, his experience with New York Dolls and seeing first-hand the music he’d been tracking from across the Atlantic reinvigorated him anew, and he returned to London with dedication to bring the punk spirit and fashion to London, and of course reap the rewards especially in the face of increased competition from shops like Acme Attractions. Though the economic prospects of championing an underground look and sound seemed dubious, so had been his stewardship of a fashion shop that was selling fetish and bondage outfits. McLaren was a punk too, he yearned to stick it to the forces of power and influence that dictated the norms of society.

Inside SEX

The impresario envisioned an opportunity to promote punk music that would also feature the store’s clothing. Feeling some urgency with the expectation that punk would break in London and follow in New York’s footsteps very soon, Malcolm set his sights on the Strand and was impressed with how the band had progressed during his time away. They’d even performed their first gig. Before he’d left for New York, the shop had produced a t-shirt that had long lists of ‘Hates’ and ‘Loves,’ one of which was ‘Kutie Jones and his SEX PISTOLS. The band adopted the phrase as their name. However, despite their progress McLaren wasn’t happy with their sound. Jones’ singing and stage presence wasn’t cutting it, and Wally’s playing was actually too good. McLaren wanted the raw and loose style of the garage punk of the United States, and a tight, proficient player got in the way. Nightingale was fired from the band and Jones was relegated strictly to guitar playing. The band needed a singer.

McLaren had first asked Richard Hell, before the Voidoids and Malcolm’s trip to New York, to come to London but that didn’t happen. Since then he’d been courting Sylvain Sylvain from New York Dolls, trying to entice him also to come to London, front a band formed around the characters of the SEX shop scene, and create a new version of the Dolls. McLaren had even brought Sylvain’s guitar with him to London and given it to Steve Jones to play. However, as the New York Dolls limped on, Sylvain held off in anticipation of the Dolls still making it big, which was a more fruitful choice than the prospects with an unformed band with Malcolm McLaren. Malcolm made a trip to Scotland and made an appeal to Midge Ure, who was in a glam band called Slik, but he wasn’t interested.

John Lydon, 1975

Some noticeable lads, all named John, had been coming by the SEX shop. One was a lanky, personable type named John Simon Ritchie, but who was known as Sid, another was John Wardle, known as Jah Wabble, and the last was a quieter John Lydon. When Lydon came into the shop with short, cropped hair coloured green and a Pink Floyd t-shirt customized by having the eyes ripped out and the words “I hate” scrawled over the band’s name, Bernie Rhodes decided to approach him. After a meeting in a pub followed by an impromptu audition back at the shop for Lydon to sing over Alice Cooper’s “I’m Eighteen” played on the store’s jukebox, there were a couple of problems. Lydon couldn’t sing and the band didn’t like him because of his smartass, brash attitude. However, Malcolm could see the spark of a lead man, the charisma in his look and expressions, and the power of his mildly suppressed rage at the world. John Lydon became the new singer. It was August 1975 and over the fall the band continued rehearsing with their new singer, which due to his reclusiveness resulted in them not yet knowing his last name. Steve was annoyed with John’s habit of spitting and inspecting his poor teeth, prompting him to declare that he “looked rotten” – and thus the Johnny Rotten name was born.

Pamela ‘Jordan’ Rook in the Let It Rock shop

The band’s fashion was drawn from the New York styles McLaren had adopted into the shop and the styles that the shop’s employees and customers were creating by adapting the fetish and bondage gear into their daily wear. Most notable of these was Pamela Rook, known only as Jordan, who had a natural propensity to dress herself up in provocative and startling fashions and hairstyles and colours. She was a leader in creating the mold for what became the London punk look and was a walking billboard for the SEX shop. The shop also had a penchant for lewd and provocative symbols and messages, to the extent that some of their patrons and employees were arrested for wearing the clothing. So, from the start, the shop and its band had an air of confrontation and danger about it.

Since Jones was no longer the lead in the band, ‘Kutie Jones’ was dropped and they became just, Sex Pistols, which McLaren liked because it promoted the shop by using the ‘sex’ name (he actually opposed Rotten’s suggestion to shorten the name entirely to just ‘Sex,’ preferring the aggressive tone of Sex Pistols). Aside from the promotional aspects of the Sex Pistols, their sound was still yet undefined. They were rehearsing by playing various garage rock and proto-punk songs and debating between a purer ‘60s pop sound, not unlike the Bay City Rollers, or a heavier, aggressive sound a la The Stooges and MC5. Johnny Rotten was instrumental in providing their direction as the evolving snarl of his vocals and his politically charged attitude, filled with disdain for the staid culture of England and the rising conservatism of Margaret Thatcher, then the leader of the Opposition in parliament, moved the band towards a sound that underpinned the his fury and, eventually, his lyrics.

The Early Sex Pistols: Steve Jones, Johnny Rotten, Glen Matlock, and Paul Cook

The Bromley Contingent

Sex Pistols played their first show in November 1975 at Saint Martin’s School of Art, where Matlock was studying, opening for Adam Ant’s pub rock band, Bazooka Joe. The problem the band hand in the early days was getting gigs. McLaren wanted to avoid the typical, tightly controlled pub rock circuit, and sought about getting gigs at social clubs and schools, often slipping the band into line-ups unannounced and without promotion. Inevitably the Pistols would end up on bills filled with pop acts and long-haired, hippie rockers. Audiences were entirely unprepared for their look and sound. Over the course of the next few months the band gathered a following of punks that would attend their gigs known as the Bromley Contingent. This included Jordan from the shop, Siouxsie Sioux (Susan Ballion), Steve Severin (Steven Bailey), Billy Idol (William Broad), and about eight others. They embodied the punk look that has become famous.

The Pistols’ shows were unruly, energetic, and constantly seeming on the verge of riot. Sid started the pogo as a dance style, combining the aggressiveness of the crowds in response to the music with the advantage of being able to see the show better by jumping straight up and down. After one such show supporting Eddie and the Hot Rods in February 1976, the band got some exposure in the magazine, NME. This helped promote them and led to better gigs, including as openers at the 100 Club in March for pub rockers the 101ers, that included Joe Strummer. That was followed by a four week residency there in May, and then a month-long tour of England that included the infamous Lesser Free Trade Hall show in Manchester (see the profile on Manchester music for more details on that show and its influence). They began headlining shows through the summer and then the 100 Club Punk Special in September. In October they signed with major label EMI and finally recorded their first songs, leading to the release of the first single at the end of November, “Anarchy in the UK.”

Signing with EMI was evidence of the pre-eminent stature of the Sex Pistols within the London punk scene. While The Saints had beaten them to the first major label signing by a punk band and The Damned and Vibrators had beaten them to the first UK punk releases, the Pistols were prepared to make a splash as only they knew how. Only the Sex Pistols encapsulated the full punk package, and EMI seemed willing to take advantage. A week after the single’s release EMI’s artist, Queen, pulled out of a TV appearance and the Pistols were sent as fill-ins, and along with them went some of the Bromley Contingent. In the cramped studio of the London evening show, Today, host Bill Grundy, who didn’t know them and was unprepared for the interview, undertook a painful and quickly unravelling interview that became a legendary moment in punk rock history. The band’s disdain for the show and the interview quickly evolved into profanity and a confrontational tone that escalated when Steve referred to Grundy as a “dirty sod” and a “dirty old man” when the host got a little flirtatious with Siouxsie Sioux. The interview ended as, prompted by Grundy, Steve unleashed a string of profanities. In 1976 England this was beyond verboten on evening television. The outrage over the event, perfectly encapsulated in the next day’s headlines, including the Daily Mirror’s “The Filth and the Fury!” with the sub-header, “Who are these punks?,” unleashed a wave of publicity that made the Sex Pistols one of the most famous acts in England.

The Pistols on Today with host Bill Grundy, with members of the Bromley Contingent in back, including Siouxsie Sioux, top right

Behind the attention gained for their notoriety and behaviour was the single. “Anarchy in the UK” was an outstanding distillation of the band’s raw, powerful sound and Rotten’s barely contained contempt for British society, proclaiming, “’Cause I want to be anarchy” and “I am an anti-Christ / I am an anarchist / Don't know what I want / But I know how to get it / I want to destroy the passerby.” There had been songs of protest and anger, more often from the gentler sounds of folk music, but this was a rare declaration of nihilism in the face of Britain’s problems with the economy and growing civil unrest related to poverty and race. If punk had lacked a defining character until then, it had it now.

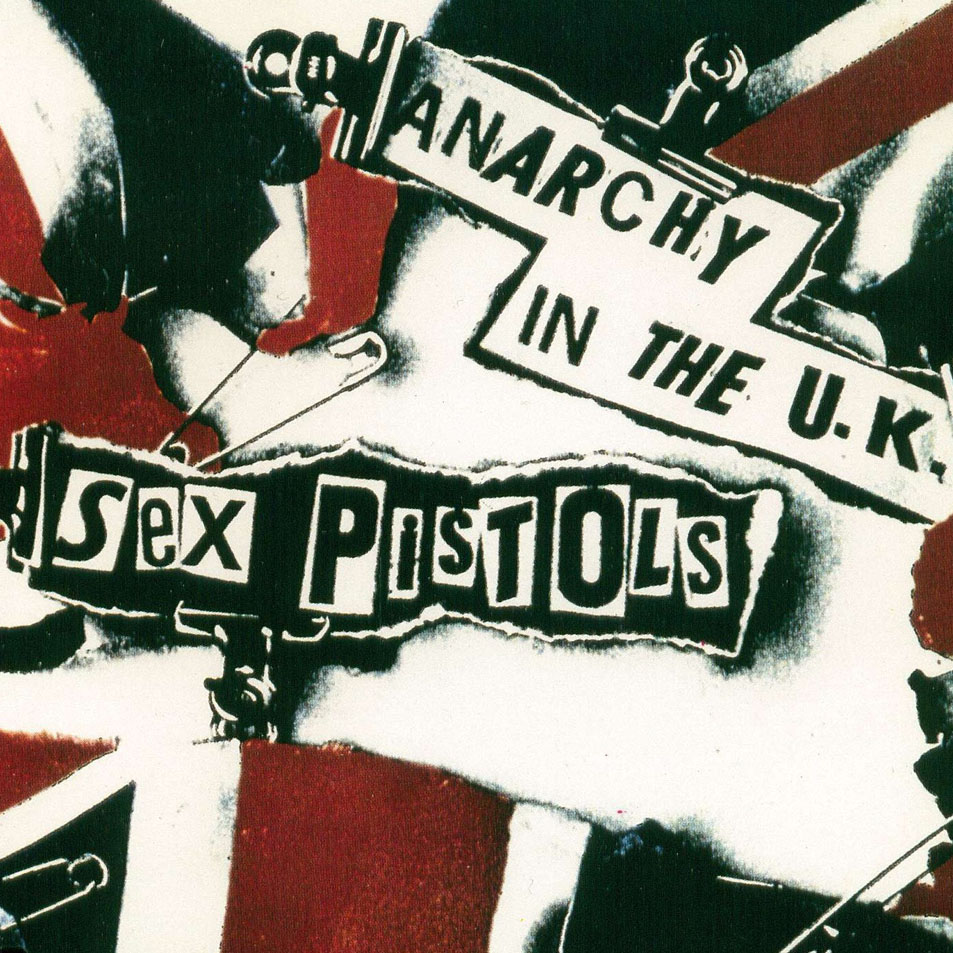

The iconic cover of the Anarchy in the UK single

Their notoriety now preceded them, and a fall tour by the Pistols, supported by Johnny Thunders and The Heartbreakers (over from the US, continuing the cross-Atlantic reinforcement of the punk scene), The Clash (in their infancy and as yet unsigned) and The Damned was either a chaotic failure or a success, depending on the perspective. Only seven of the twenty scheduled shows actually happened as the organizers or local authorities cancelled the shows, indicative of the level of outrage and protest against the band after the Grundy interview. The Damned were kicked off the tour very early by McLaren, despite his having managed their prior incarnation – apparently there was no love lost between them as punks tend to be a sensitive and reactive bunch. Yet, despite this seeming evidence of failure for the tour, from a punk philosophy this was fantastic since it solidified the Sex Pistols and punk rock as renegades, challengers of the status quo, and agents of disruption to the ‘stiff upper lip’ culture of Britain.

So, whether they played or not the Sex Pistols were building punk as an attractive option for many of the working-class young across England. You didn’t need to be a virtuoso to play, you didn’t need to wait for a record label to sign you or someone with cultural authority to anoint you as acceptable to the musical community, you just had to have energy, attitude, and a willingness to put it out there, consequences be damned. And in so doing could give voice to the frustration and dismay the youth were feeling in the economic malaise of mid-70s England. This was the defining character the Sex Pistols and the British punk scene established over the latter half of 1976.

Final Solution \ Pere Ubu

In the US, the trends were similar but, perhaps due to its size and geography, the proliferation of punk was slower and more fractured. No one was making headlines in the US as a punk, except of course, the Sex Pistols who were a faraway curiosity to be tutted over in America as much as in England. But as 1976 moved to its conclusion, inevitably the punk sounds were being picked up in US locales outside of New York City. In the same way the Sex Pistols tour spread the word across Britain, The Ramones similarly were leaving their impact as they played cities around the country, seemingly sparking punk scenes overnight as they went.

However, as much as the core characteristics of punk musically today is that of fast paced, short, guitar driven songs filled with aggressive or shouted vocals, it hasn’t always been that way. In 1976 there ensued the endless debate on exactly where the boundaries of punk lay. Does the band play fast enough? Are they angry or impudent enough to challenge people’s sensibilities? Do they look the right way? Even punks debated, with Johnny Rotten being dismissive of The Ramones because of their hippie-like long hair. Like any genre, there are purists who seek to maintain some clear order regarding these things, and inevitably there is always confusion. Often it is the media, in which the topic is approached by outsiders that are curious but don’t fully understand the emerging scene, that will generalize and bend the boundaries in order to simplify the context for readers. Therefore, as punk rose in attention, which in 1976 meant moving from complete oblivion to minor, niche awareness, the idea of which acts were ‘punk’ was very debatable. I’ve struggled, even forty-three years later, in deciding what to include on this list. Punk is a music, an attitude, and a fashion, all of which have fuzzy borders.

On the southern shores of Lake Erie, the punk spirit had always been there and continued to thrive. It had been out of the suburbs of Detroit that punk had been sparked through The Stooges and MC5, and there were many characters and bands working in Ohio that were building the punk attitude. Once such band had been Cleveland’s Rocket from the Tombs, who played for two years but never released any music other than a bootleg cassette. In 1975 the band broke up and its members went on to form three bands: The Dead Boys, The Saucers, and Pere Ubu.

Pere Ubu was formed in 1975 by singer David Thomas and guitarist Peter Laughner from Rocket from the Tombs, who joined with bassist Tim Wright, drummer Scott Krauss, and keyboardist Allen Ravenstine. In true DIY spirit they formed their own label, Hearthan (eventually changed to Hearpen), and started releasing singles. The first was “30 Seconds Over Tokyo” in 1975 and the second was “Final Solution” in 1976 (time of year is unknown). Both songs were reflections on the destruction of World War II, though “Final Solution” could be interpreted more broadly about ostracism, racism, and conflict in general, though its title obviously was a tie to the Nazi pogrom.

Pere Ubu

Was Pere Ubu punk? They didn’t wear ripped clothes or wear coloured hair or Mohawks (US bands didn’t go for that much) and their music was aggressive and different but didn’t sound like The Ramones or Sex Pistols. “30 Seconds Over Tokyo” was disjointed, raw, plodding, mostly vocal driven but carried on a repeated guitar riff and overlaid with fragmented, unmelodic guitar sequences and chaotic interludes, and was over six minutes long. However, it’s B-side, “Heart of Darkness,” was a sparse, dark, mid-tempo tune but held more to the standard rock composition aside from Thomas’ slightly unhinged vocal, especially over the last section. In 1975 anything that was raw, guitar driven, indie and unpolished would be labelled as garage rock or, retroactively, proto-punk. Pere Ubu simply defied classification at that point. “Final Solution” was a smoother, more refined song that again was mid-tempo, laid on a solid drum and bass foundation, and marked by Thomas’ aggressive vocal and washes of heavy, assertive guitar with psychedelic notes. It had all the attitude and energy of punk but didn’t conform to the emerging stereotype. In Wikipedia, Pere Ubu’s genres are listed as art punk, post-punk, art rock, and experimental rock. In the end, did it matter? “Final Solution” was a great song, and it showed punk culture was happening outside of New York.

Hot Wire My Heart \ Crime

Crime

In similar fashion there was the band, Crime, out of San Francisco. As if often the case with American culture, emerging, experimental, progressive scenes of art and culture tend to generate from the coasts and work inwards. The Detroit and Ohio scenes for punk were an interesting exception to this historical trend. Crime was started in 1976 and, though San Francisco had been ground zero for the hippie, folk and psychedelic scene of the 1960s, had still been a place for more aggressive forms of rock to flourish through the ‘70s, such as with The Flamin’ Groovies. Actually, that band’s bassist, Ron ‘The Ripper’ Greco, was an original member of Crime.

Listening to “Hot Wire My Heart,” their first single released in late 1976, it was evident they were a band evolved out of the garage rock sound of New York Dolls. Rough and ready, loose, and propelled with aggressive guitars, the song had punk markings blended with a classic, garage rock vibe. Crime would release three singles, with the second in 1977 and the third in 1980 before disbanding in 1982. Their fuller discography has been captured in various bootlegs and compilation releases over the years, giving better exposure to their sound which had an undoubtable influence on the imminent explosion of California punk.

As we conclude this list there is a common misconception about punk I’d like to address that I hope, after hearing these songs, has been dispelled, and that’s the idea that punks were poor musicians. Certainly, the DIY ethos resulted in many bands starting out when they were just learning and playing early shows in which they were pretty awful and got by on moxie and energy, but in terms of what got recorded and rose to prominence, it was always because of talent and accomplishment.

Like all music, punk was about feeling; but in its case the feelings were anger, disillusionment, protest, and disruption, or just fighting the malaise of the boring and typical by generating an energy and elation that couldn’t be found elsewhere. By necessity, the music had to be direct, simple, complete, and impactful, something that guitar and drum solos, introspective, moody ballads, sparse acoustic numbers, or lengthy, orchestral, indulgent and virtuoso meanderings couldn’t achieve. Perhaps the punks weren’t talented in the way prog rock or classic rock guitar heroes were, but they could still play and get their message and sound across effectively and write great sounding tunes. Punk thrived at first in live settings and the early recordings sought to capture the live spirit in the studio and therefore purposely lacked polish and the refining touches of higher production and mixing. The songs were meant to be raw, quick, filled with a sense of danger and near-unbridled passion, very human, and accessible. They were songs the average person was meant to feel they could make, that they could sing and relate to, and of course throw themselves around to release the unspent energy of their frustration. That was how punk connected and grew. But make no mistake, under all the noise and shouting, there was harmony, there were tightly constructed and well-played rhythms, and there were many great songs.

As I’ve been writing this profile, an incident occurred between the last surviving Ramone, Marky (who in 1978 replaced Tommy on drums after the third album) and John Lydon, reminding us of a long running feud. An ever-present debate since punk’s arrival has been what is truly “punk.” In this case, Lydon, from the beginning, was dismissive of The Ramones and never considered them punk. For Johnny Rotten, punk wasn’t just about the sound, it was the attitude, the clothing, the behaviour, and the message. Certainly, The Ramones were essentially a pop band played very fast – the Beach Boys on speed – but did that negate their punk credentials? This profile, as all do on Ceremony, focuses on the music and its evolution and character, and in that regard it’s irrefutable The Ramones were one of the first and most prolific punk acts by virtue of their sound. I’ll leave it to you to judge their broader credentials. It should be noted that musically, there were many subsequent punks (and broader critics) who were as dismissive of the Sex Pistols, considering them more of a novelty act than a serious music group. Like any genre, the boundaries of punk are blurry and debate can be endless as to who fits and who doesn’t, and often it’s just a relative determination so the starting point can change the result. Regardless, by the end of 1976 punk was an established and growing genre and it was igniting a wave of access and creativity from young people across North America, the UK, and Europe. It had arrived.

This profile built off the Builders of Modern Rock playlist and is followed by the playlist, 1977: The Birth of Modern Rock, where the story of punk rock continued as well as exploding into many new styles of modern rock.